riding feature

STILL TAKING IT TO THE LIMIT

Forty Years After Breakthrough Film Debuted, Producer Remembers Capturing Racing History

By Peter Starr

In 1980, the motorcycle racing world cast its gaze on Daytona Beach. The toughest competitors from four continents came to Florida’s Atlantic Coast to ride the most sophisticated machinery that era had to offer.

And for the premiere of a movie about the sport.

Kenny Roberts, Steve Baker, Barry Sheene, Mike Hailwood, Roger DeCoster, Russ Collins and Bruce Penhall were among those featured in the film.

All were vital forces in motorcycle racing—the best of the “good ol’ days.” Now, they are largely the silver wraiths whose accomplishments contine to define the sport.

That was 40 years ago, which is several lifetimes in racing—few professional careers span more than 10 years—but just one lifetime for Take it To The Limit and for its creator, me.

Despite positive reviews and festival honors, Take It To The Limit never received as widespread a distribution as it may have deserved, largely because of the usual Hollywood story: Producer makes film; distributor shows film; film makes lots of money; distributor runs away with money; film is buried in legal hassles; producer never sees money; and film languishes in near oblivion.

Much of that story is covered in detail in my book, Taking It To The Limit: 20 Years Of Making Motorcycle Movies.

The promises of youth, in filmmaking as well as motorcycle racing, so often go unfulfilled. In this film, however, we captured some of the most iconic moments in motorcycle racing history.

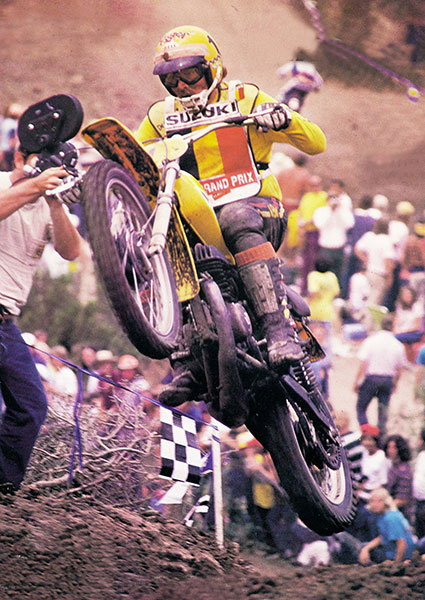

▲ Roger DeCoster, a five-time world champion by the time the movie was released to the public in 1980, was filmed during Trans-Am events in the United States during the 1970s.

Photo by Peter Starr Productions

When we were shooting—film, not video; the latter was still a decade away—we were just out to make the best motorcycle movie we could, standing in the right spot, pointing the cameras, rolling the film and hoping that our chosen riders hit pay dirt that day.

We weren’t disappointed.

Roberts, Baker, Hailwood and the others performed some of the most memorable feats on race days. If luck in motorcycle racing is 90 percent preparation, the percentages in filmmaking are no different.

From the opening scenes of David Emde riding a Yamaha XS1100 at terrifying speeds along a closed road north of Ojai, Calif., there was little doubt as to what this film was about.

The title is more than appropriate. We were at the Indy Mile in 1975 to film Rex Beauchamp, Corky Keener and Gary Scott when Roberts stunned us—and his competition—with one of the most exciting rides in flat track history.

It was a magical moment, and we were lucky to capture it. When Roberts returned to Indianapolis in 2009 to ride a replica of his race-winning Yamaha TZ750, fans were screaming to relive the experience with him.

The yowl of Roberts’ four-cylinder two-stroke amid the thundering Harley-Davidson XR750s commands a part of my memory equal to that of Bob McIntyre fighting it out with John Surtees on the 170-mph drop from Kate’s Cottage to Creg-Ny-Baa at the Isle of Man in 1957.

And who could have forecast Steve Baker’s performance in England in ’76 at the prestigious Race of the Year? Pitted against some of the world’s greatest road racers, including Phil Read, Giacomo Agostini, Mick Grant and Sheene, Baker so dominated the event that we had to edit the film to make it seem more exciting.

I had known Baker and Sheene for some time, and it gave me great pleasure to bring them together for this film sequence. Baker is still with us and as modest and unassuming as ever, considering he was America’s first road racing world champion. He was one of the few riders who gave Roberts fits when they raced each other.

Sheene passed away from cancer in 2003. I last saw him only a few months prior to his death when he won a vintage race at Donington Park riding a Manx Norton with the same skill and style that made him a two-time world champion and the “darling” of enthusiasts.

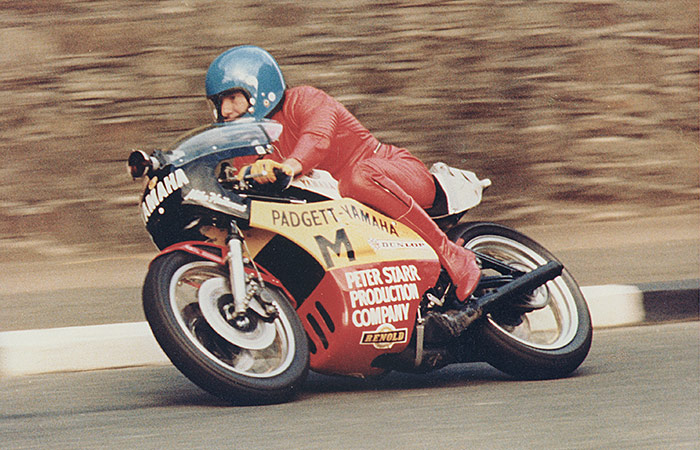

▲ Mike Hailwood hustles his Yamaha TZ750 through Union Mills at the Isle of Man. Note the bulky film camera poking through the windscreen, a Stone-Age tool, compared to today’s digital units.

Photo by Peter Starr Productions

Hailwood’s return to the Isle of Man in September 1977—exactly 10 years after he had last competed there and 19 years since his first appearance on the mountain circuit—was the stuff of legend.

What we captured on The Island for this film, with special thanks to Rod Gould—himself a world champion in 1970—was truly remarkable, not to mention fortuitous. It laid the foundation for Hailwood’s racing return and subsequent victory in 1978.

Emde was a relatively unknown racer at that time, but he contributed a lot to the opening scene of the film, as well as the Roberts-at-Riverside sequence. He stepped in to ride our Yamaha 0W31 camera bike following Skip Aksland’s Turn 9 get-off.

I am still captivated by the memory of chasing and leading Emde, both of us on XS1100s, at 130-plus mph along a two-lane road north of Ojai, closed for our use by the California Highway Patrol. I was saddened greatly when Emde succumbed to injuries suffered in a street bike crash in 2003.

After the Hailwood sequence, the section of Take It To The Limit that is recalled most often is Russ Collins at the drag strip. This pioneer of two-wheel rocket ships pointed his 600-horsepower, twin-engine “Sorcerer” down long-defunct Orange County International Raceway and came within the proverbial cat’s whisker of a 200 mph terminal speed carrying two of our highly specialized cameras.

And that was 1978!

The young men in the film pushing Collins and his motorcycle back to the starting line after his burnouts? Terry Vance and Byron Hines.

Yes, drag racers are quicker today, but none seem to have captured our imagination as Collins did, both for his engineering skills and his bounteous bravado.

One of my most gratifying achievements with the film was securing participation of major music talent for what became a platinum soundtrack.

At the time, there had never been a documentary with a hit soundtrack, let alone one produced using the then-new Dolby stereo technology. Most music stars had not yet put a value on a film using their music. The acts that worked with us were generous with their music and their time.

Foreigner provided three of its most popular hits after the members of the group, two of whom were motorcyclists, learned about the content of the film.

Jean Luc Ponty came to see a rough cut of the movie, then agreed to let us use three of his hits. Tangerine Dream had no idea that its record company licensed us the wonderful instrumental piece, “Stratosphere,” a song suggested to me by Mike Nesmith of The Monkees fame.

And John McEuen, formerly the banjo player of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, whom I had known since my rock-and-roll days in Canada in 1967, was only too pleased to help with his very unique approach to acoustic music.

Folk balladeer Arlo Guthrie was the only musician who appeared in the film. Guthrie rode his motorcycle around the beautiful country lanes of his home in the Berkshire Mountains of Massachusetts, even though it was still winter and quite cold when we filmed that sequence.

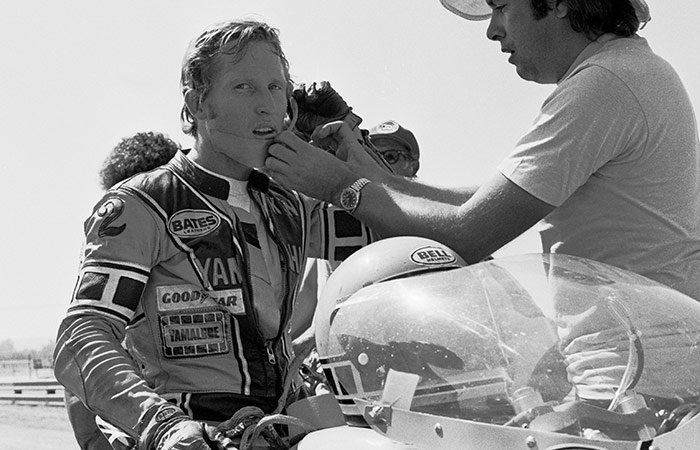

▲ Kenny Roberts was fitted with a special microphone to record his thoughts as he cut hot laps at Riverside International Raceway in Riverside County, Calif.

Photo by Peter Starr Productions

Guthrie recorded a special version of his “Motorcycle Song,” for which we created an equally unique “claymation” piece that originally paved the way for the film, much like cartoons used to precede movies.

Unfortunately, in our marketing screenings prior to the release of the film, no one understood why it was there. So, the cartoon was shortened and relegated to the back of the film, ultimately becoming part of the credits. I still think it was a great idea, brilliantly executed by animation expert Jon Wokuluk, and I included the complete five-minute version with the release of the DVD.

My memories from those days are many and colorful, and I have always been grateful for what my crew achieved. To have made a feature film and had it shown across the country in theaters, let alone win major film festivals, is an accomplishment the likes of which are hard to communicate.

To have brought this film to life with some of the icons of that era is perhaps the most rewarding achievement of my career.

I recently was asked how I felt about the movie’s success—or, as some would see it, lack thereof. That’s as tough a question as I have ever faced. Making the movie, and breaking new barriers to bring it to the big screen, still gives me that warm inner feeling of a job well done.

Accepting the awards when the film was honored at the Houston (silver) and Chicago (gold) International Film Festivals gave me a sense that my filmmaking career had truly arrived, and that Hollywood would be beating a path to my door. That never happened, in large part because of the ungodly legal mess left when the distribution company, in whom I had placed an inordinate amount of trust, ran off with the money.

Forty years on, I am looking at showing the movie one more time. After that, who knows? I have interviewed many of the people who appeared in the film to add a retrospective look at those stars who were the backbone and attitude of Take It To The Limit.

This has been a strange and complicated road, but I am proud that only two films in this genre have enjoyed wide cinema distribution. Take It To The Limit was one of them.

Given what I have learned, would I like to make a sequel? You betcha.

Peter Starr is a member of the AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame Class of 2017.

Photo by Peter Starr Productions