riding feature

Lessons Learned,

50 Years On

How A Humble Little Honda Provided The Best Riding Start

By John L. Stein

Exactly 50 years after learning to ride on a red 1967 Honda CL90, I’ve come to realize that almost everything I really needed to know about motorcycles came through this humble 8-horsepower street scrambler.

Flash back to June 1970, and the motorcycle boom in America was on. The Honda CB750 Four had just debuted, as had Kawasaki‘s audacious 500cc H1 two-stroke triple. And all manner of dirt bikes were flooding in from Germany, Japan, Czechoslovakia, England, Spain, Italy and Sweden.

And so many magazines like Cycle, Cycle World, Motorcyclist, Modern Cycle, Popular Cycling and Cycle Guide arrived on the newsstands monthly like a fresh hit for junkies.

Go Earn It

Months of appealing, arguing, cajoling and pleading with my parents—backed by decent scholastics and a demonstrable work ethic involving riding a Schwinn Varsity all over our hilly community to mow lawns, clean houses and flip burgers—sealed the deal.

What I really wanted was a Hodaka, the coolest, best-looking street-legal enduro of the time. My dad, however, steered me toward Honda instead—and, specifically, the Scrambler 90—bought used from a UCLA grad for $200.

In hindsight, although my dad didn’t know much about bikes, he couldn’t have picked better. I’m convinced that no motorcycle available at that time was better matched to this skinny 16-year-old.

That bike took me 18,000 miles in 18 months before I graduated to a 250cc Ducati, along the way conferring a lifetime skillset. Here are my favorite lessons:

Lesson 1: Where Danger Lurks

Besides having me earn every dollar of the Honda 90 price—no credit given, no loans, no IOUs—my dad sent me pedaling the Schwinn to the local library to learn about how people get hurt on motorcycles.

There, I discovered the worst occurred in intersections during rush hour, when cars turn in front of motorcyclists. They just don’t see you. This prompted me to devise a game called, “I’m it,” in which no car could see me and, worse, they all would try to run over me.

Acerbic? Yes. Doubting? Yes. But I’m convinced that riding with such suspicion saved me on more than one occasion, and I still play the game in 2020.

Tip: Watch the driver’s head and the car’s front wheels.

Lesson 2: Learn Slowly

Initially, I was forbidden from using the four-lane, 35-mph road that bisected our town. So, I had to find alternate routes to visit friends, access trails on the outskirts of town or just ride around.

The parents’ instincts were solid, as neighborhood streets reduced speeds and, thus, kinetic energy, increased reaction time during potential incidents and lessened stopping distances, all of which reduced the chance of injury if something went wrong.

Slow is good, while learning.

Lesson 3: Look for Traction

Riders must learn terrain when they begin riding off-road because dirt, gravel, rocks, sand, mud and stream crossings have different textures and characteristics, some which will happily send you flying—or sliding.

My harsh lesson in reading terrain, however, happened at an intersection of two paved neighborhood streets, separated by a concrete swale.

The swale’s purpose was to channel water across the intersection, but the water carried leaves with it, which laid in wait like a pack of hungry gators alongside an Everglades backroad.

To a teen, zooming through the swale and scattering water and leaves looked like fun. Little did I know how slippery water and leaves in a concrete swale would be. Down went the Honda, leaving its rider sliding along the asphalt, savaging both knees and hands.

Forever after, gloves became a part of my riding kit, and I regarded street surfaces nearly as suspiciously as I regarded cars.

Fifty years later, the scars still exist, but I’m happy to report that was my first and only fall on the street.

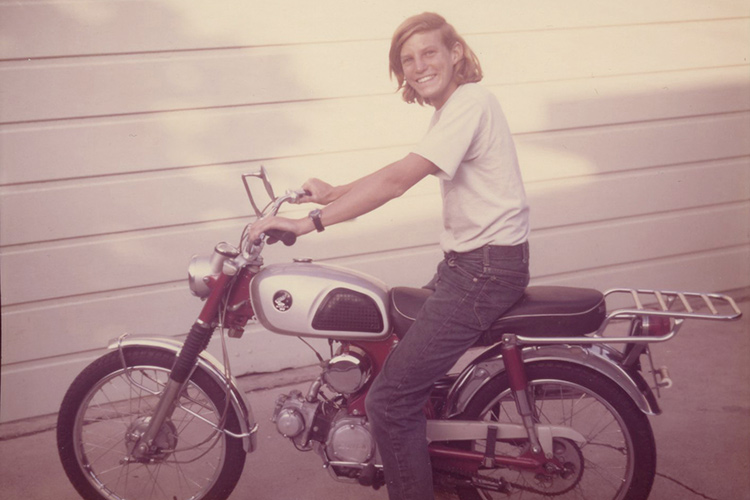

▲ Seeing photos of Paul Smart racing inspired learning to hang off the 8-horsepower Honda CL90, shown here in Malibu circa 1971.

Photo from the John L. Stein Archives

Tip: Dress to crash, then don’t.

Lesson 4: Master Momentum

On a big bike, you needn’t worry about gaining momentum before hills, but the Honda 90 and its 59-mph claimed top speed was slower than the slowest Volkswagen. This kind of kinetic anemia required planning ahead and using horsepower efficiently.

This truth emerged after school one day, when a friend and I discovered a local rider—a decade older, with a real job—with a Triumph 650 scrambler eyeballing a dirt embankment in a hilly neighborhood. He took a shot and accelerated hard, the big twin roaring.

But, surprisingly, the hot-rod rider couldn’t make it. The Triumph dug

in partway up, and he had to retreat in defeat.

My turn. Using whatever skills I had acquired in coaxing the little Honda up local trails, I was able to conquer a dirt slope that the heathen 650 couldn’t.

My epiphany that day: Small bikes are not inferior to big bikes; in some cases, they actually are better; and, in all cases, better skills supplant lesser skills. To this day, I still plan my moves, practice carrying momentum smoothly and believe low power equals high learning.

Lesson 5: Do It Yourself

Given my teenage proclivity for trail riding, I discovered that some engineering aspects of the street-focused CL90 scrambler were not intended for real off-road use.

One was the fork, which bottomed regularly in severe use. Experimenting with different fork oils made it at least acceptable. Another was the twin shocks, which lacked both damping and spring rate.

As a cheap solution, I bought my buddy’s Kawasaki 175 shocks and adapted them to the Honda. Were they a good match? Hell, no. But they didn’t bottom under severe use, and that was a step forward.

Other mods included high-mounting the front fender to keep it from packing with mud, making nonslip cleated foot pegs and fabricating a side stand, which tucked out of the way and would not flop around like the stock center stand.

All these were made in shop class during my senior year. The mods were free; they just took a hacksaw, file, hammer and vise (OK, and an oxyacetylene welder).

Hey, youths: Try it sometime!

Lesson 6: Jumping Johnny

In a local canyon was a steep hill climb that could, with sufficient speed, double as a downhill leap. And so we buddies accepted the challenge—up and down, down and up, again and again.

This missive doesn’t purport to serve as a primer for jumping dirt bikes. But, in my case, all the jumping taught me what works: Adopt an “attack” position, akin to that of a football defensive end; keep your mass over the center of the bike; and go easy on the throttle upon launching.

Smooth liftoffs mean smooth sailing.

▲ Now, a mere half-century later, that skill set helped tame Kawasaki’s 200-horsepower Z H2 at Las Vegas Motor Speedway.

Photo courtesy of Kawasaki

Lesson 7: Break It, Fix It

When you earn only $1.50 an hour, all motorcycle parts purchases are significant, and paying for shop labor is out of the question. Therefore, when the Honda developed an electrical fault, I had to figure it out myself.

A 30-mile ride on the Schwinn to buy a new rectifier turned exasperating, because the Honda’s rectifier wasn’t bad. it was the battery.

Ditto when the piston scuffed while riding back from the Greenhorn Enduro. That repair required a new piston and rings, cylinder boring and gaskets—and forming new skills.

The skill set continued growing with chain maintenance, replacing lightbulbs and tires and even making a new seat cover on a sewing machine after the original split open. Yeah, bikers can sew.

Maybe the Honda’s greatest service drama was that its pressed steel frame cracked in three places near the engine mounts, likely due to jumping—well, landing. But because I had already learned to weld, the repair came out great, especially after refinishing it with Lubri-Tech spray lacquer coded just for the bike.

From electrical diagnostics to engine rebuilding to fabrication and welding, that Honda taught it all. Self-reliance, check.

Lesson 8: Learn to Suffer

Motorcycles are fantastic connections to the environment. In the morning, we may feel and smell the air and relish its warmth, only to later curse the rain and suffer in the cold and wind.

Aboard the Honda 90, with only a parka for protection, I got what I got. So, with no money for fancy riding gear, on rainy days, plastic bags rubber-banded over the knees helped keep pants dry, gardening gloves helped keep hands warm, and a neck scarf mom knitted helped keep air out of the jacket.

Riding means suffering, to some extent, so I believe all those miles on that little bike spent enduring physical suffering were a great apprenticeship for life: Achievement requires commitment, and whining never helps.

▲ Same skills, different decades: Up on the pegs, centered on the bike and isometrically strong is always a good way to fly.

Photo courtesy of BMW

Lesson 9: Brake First, Ask Questions Later

Following a friend on his Bultaco Metralla down a twisting road, I discovered neither the Honda 90’s brakes nor its rider’s situational awareness were up to snuff. I ran out of brakes before an off-camber hairpin and smacked into a curb, fortunately without a fall or damage.

But that incident forever changed my approach to braking. Consider this: Braking is like shooting baskets or hitting golf balls, wherein you apply the exact force necessary to reach the target. Except in braking a motorcycle, you use the force necessary, not to hit a target, but to arrive at your turn-in point at the correct speed.

It’s fuzzy logic, to be sure, and requires much practice. But remembering that unplanned meeting with a curb made me determined to master the methodology of braking. And, I did.

Lesson 10: Wheelie Power

Next to jumping or pitching it sideways, there’s nothing more fun on a bike than wheelies. Years of bicycle practice imparted the basics, but that didn’t help much on the sluggish 202-pound CL90.

▲ A local canyon providing a great place for jumping the Honda.

Photo from the John L. Stein Archives

But I did learn something important: Wheelies are about balance and finesse, not power. So learning to drop the clutch, yank the bars and slide my weight back eventually produced long Honda 90 wheelies on demand.

Finding the balance point was the trickiest part, because there was no power reserve to keep the front wheel aloft if the balance failed.

Tip: Learning to wheelie uphill helps; you get to the balance point quicker, and the hill serves as a natural brake when you feather the throttle.

Lesson 11: Look Before You Leap

Early Sunday mornings (as in, 1-5 a.m.) were spent assembling and folding the chunky Los Angeles Times in a downtown alley so the delivery guys could get them to subscribers by dawn (it was great money, $2 an hour!).

One dark morning, the papers were late arriving from the printer. For amusement, I decided to try jumping down a steep dirt embankment separating the upper shopping district from our low-lying alley.

There was no light, and I didn’t see the big dumpster with a jagged metal piece jutting from the side. After completing the jump, my left hand snagged this medieval blade and virtually tore my middle finger off, twisting it 90 degrees, causing a spiral fracture and shearing off the fingernail, for good measure.

The surgeon said I would never play concert piano. He was right, but it wasn’t because of the finger, which is fine today.

Tip: Fly Visual Flight Rules, like pilots.

Lesson 12: Chicks Like Bikes!

As it turned out, girls like motorcycles, too. And during the transition from high school to college, I learned the Honda 90 seemed to them a safe, friendly appearing ride. I’ll leave it at that.

Sixteen Again

Now a half century since that first Honda 90, I still marvel at having ridden the original so far, and at everything it taught me. And when I say the lessons were real, I really mean it. My last motorcycle writing assignment before the coronavirus lockdown was track-testing a 200-horsepower (25 times the Honda 90’s output) supercharged 2020 Kawasaki Z H2 at Las Vegas Motor Speedway.

There, looking and thinking ahead, choosing smooth lines, feeling for traction, staying centered on the bike, managing wheelies and braking and being efficient, smooth and steady were paramount at 160-plus mph on the high banks.

And you know what? It all worked out fine. So, wherever you are original little Honda CL90, thanks tons. I definitely owe you one.

John L. Stein is an AMA member from Santa Barbara, Calif.