Main Feature

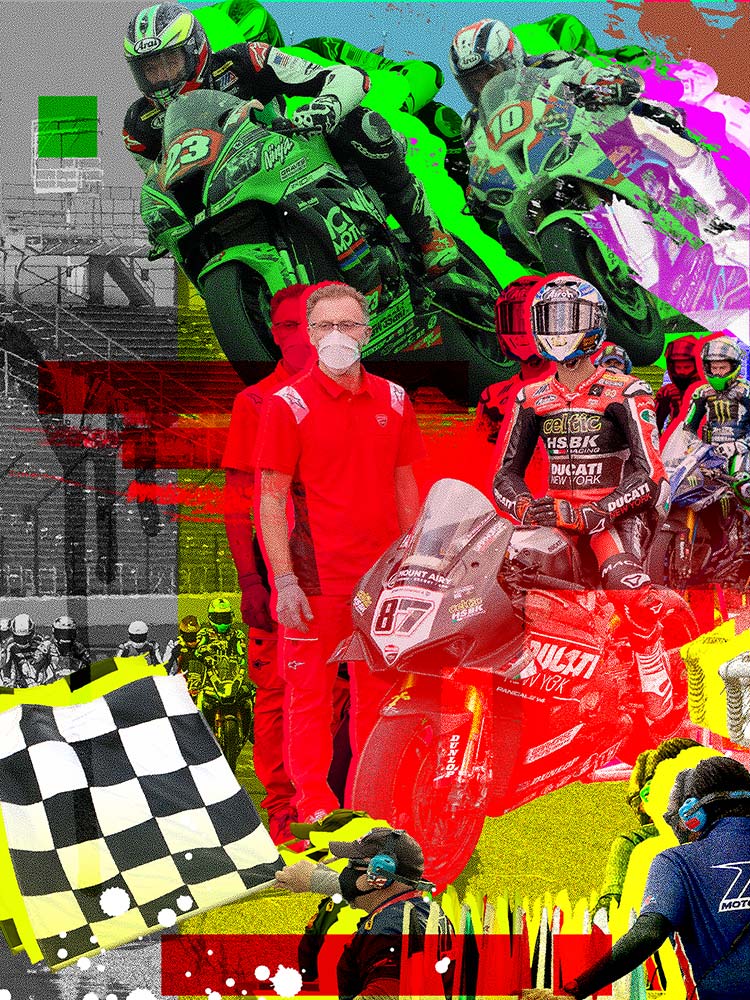

Let’s Go Racing

Task Force Plan Got Americans Back On The Track

By Jim Witters

When the coronavirus pandemic reached American shores and swept across the nation in the spring of 2020, citizens faced mandates and curfews, schools and businesses closed, international—and in some cases, even interstate—travel halted, recreational activity slowed, professional sports leagues shut down and competition events stopped.

Motorcycle racing was not spared.

Professional and amateur events were canceled or postponed as state and local governments and health officials limited the size of gatherings and instituted restrictions that made staging a small, local amateur event impossible, let alone an AMA Supercross event that might draw 40,000 fans.

Faced with a loss of fans, participants and income, the motorcycle racing community pulled together as never before, pooled its knowledge, talents and expertise, and created the Safe-To-Race Task Force.

Safe-to-Race Task Force Members

AMA:

Bill Cumbow, Mike Pelletier,

Alexandria KovacsDAYTONA MOTORSPORTS GROUP:

Gene Crouch,

Jared Johnson and Joey MancariFeld Entertainment:

Dave Prater

Ignite Partners:

Ken Hudgens

and Tim MurrayMotorsports Reg:

Brian Ghidinelli

and Chris RedrichMX Sports:

Tim Cotter,

Jeremy Holbert and Jeff CanfieldMX Sports Pro Racing:

Davey Coombs, Carrie Russell and Roy Janson

Mylaps:

John Dains and Gabe Ellett

Pro Motocross Organizers:

Amy Ritchie and Alan Verlander

USMA:

Robert Johnson

and Shawn StewartRider Representative:

JH Leale

The 24-member task force met regularly in Zoom video conferences and hammered out the Race Resumption Plan and Best Practices Toolkit, which proved to be the vital resource organizers and racers needed to resurrect their sport.

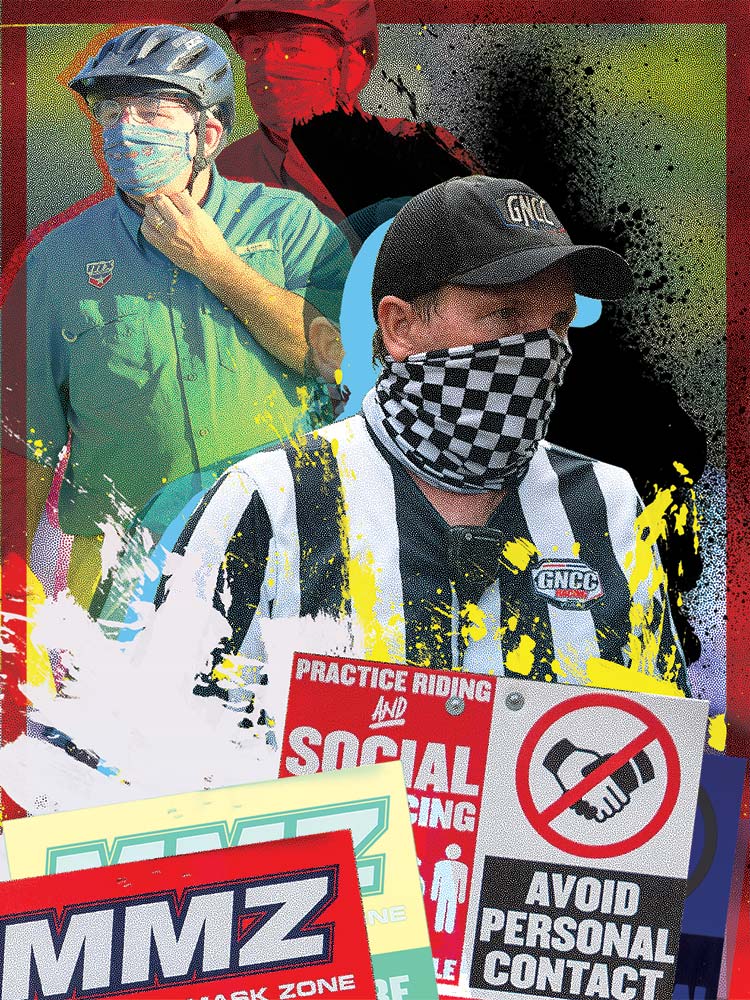

The information, which can be found at americanmotorcyclist.com/covid19resources, covers race operations, employee wellness, event messaging, signage and more. These guidelines were essential to the return of sanctioned motorcycle competition at all levels.

For their determination to revive their sport in the face of a viral outbreak that has infected more than 11 million Americans and caused the death of a quarter million, the members of the Safe-To-Race Task Force are the 2020 AMA Motorcyclists of the Year.

The AMA Motorcyclist of the Year is the individual—or group—who has had the most profound impact on the world of motorcycling during the past 12 months.

“What I think is so important about the task force was that we were all in uncharted territory,” said JH Leale, president of Ricky Carmichael Racing and the rider representative on the task force. “This plan made it possible in the absence of government guidelines to get back to racing.”

The strength of the Safe-To-Race Task Force lay in the unity of purpose and commitment to the cause of every individual involved.

“The challenge we faced and everyone coming together really stand out to me,” said AMA Director of Racing Mike Pelletier, a member of the task force. “No matter what their background, no matter what their interest was, everyone focused on one targeted thing, and that was saving what we had and getting racing going.

“And, too, seeing the people showing up with, whatever, you name the guideline, but they were just genuinely happy to be back racing at an event. That really stood out to me.”

Building The Team

It was mid-March, and Racer Productions had just completed the Grand National Cross Country Series’ third round in Washington, Ga., when the coronavirus shut down the nation.

“We didn’t know what was coming,” said Carrie Russell, president of Racer Productions and CEO of MX Sports Pro Racing. “We were watching closely, monitoring all states, and it became clear to us that the shutdown was going to be nationwide. But, then it became a state-by-state decision how to reopen and when.”

“And because we are the organizers, the managers, of the AMA Amateur National Motocross Championship at Loretta Lynn’s, we were very concerned about the result of the shutdown on the Area Qualifiers schedule,” Russell said. “We were right in the middle of the area qualifiers. We had finished eight. And then we got shut down. And that completely compromised, jeopardized, the entire Loretta Lynn’s program, which is so important to amateur motocross.”

Amateur and professional racers, organizers, families and communities across the country worried about their pastime, their passion and their livelihoods.

In May, two months into the shutdown, Russell and MX Sports Director Tim Cotter got together via Zoom calls with Roy Janson, competition director for MX Sports Pro Racing, and Davey Coombs president of MX Sports Pro Racing.

“We said, ‘What are we going to do? We need a Plan B, C (it ended up D) for Loretta Lynn’s,’” Russell said. “And we decided that we needed some other people on our team. And we definitely needed the AMA represented.”

Russell and Cotter added Pelletier and AMA Director of International Competition Bill Cumbow to the team, along with Cotter’s brother, Britt, a former Marathon Oil executive, who would be the statistician.

This new Race Leadership Team began meeting each Monday via Zoom to try to determine when to return to racing, how to return to racing and what form racing would take for the remainder of the year.

“And it’s not just us and our events, but the whole country,” Russell said. “How do we get the whole country racing again?

“We decided that, for us [at MX Sports], we have a team that can help us. But these other promoters, they don’t. Some of them, they don’t have staff. They don’t have access to certain information that we do. And, so, we decided that we needed to build a team of experts that could give us their advice and create a path to get back to the racetrack.

“And we came up with the Safe-To-Race committee.”

The leadership team invited people throughout the motorcycle racing industry, the healthcare field and government service to lend their expertise.

Tim Cotter said the subcommittees included 48 people, “all of them with credentials.” Dr. Nona T. Colburn, an official who produces white papers and helps set policy at the National Institute of Health, is a motorcycle racer who was happy to help.

“We knew that our company, through our events, does a lot of work in Crawfordsville, Ind.,” Cotter said. “Through that relationship, we got to know the health department and the homeland security department, and so we reached out to them. They had skin in the game. They helped us draft the plan.”

The leadership team divided the volunteers into subcommittees and handed out assignments.

“You have two weeks to create protocols that meet the health and safety guidelines of the [U.S. Centers for Disease Control] and report your findings back to us, and then we will take all those subcommittee reports and combine them into one plan,” Russell told the group.

Pelletier said the assembled group faced a difficult task.

“The problem we faced was each town was different. Different states, different breakouts, different numbers were rising, different health departments,” he said. “It was incredible. There wasn’t one set guideline for the whole country. It was county by county.”

When the subcommittee reports came back, Russell—an attorney—devoted 12 hours a day for four or five days compiling the draft plan.

“The result was the Safe-To-Race Toolkit that we then issued throughout the industry for anybody to use,” she said. “And it, basically, was a step-by-step instruction manual on how to get approval, get back to the racetrack and conduct your events in a safe manner that would be satisfactory to the local health organization and also be safe for your staff and safe for our racers and their families.”

Putting The Plan To Work

With the plan in hand, the next job was getting it to the event and series organizers and explaining how it could work for them.

Cotter already communicated weekly with Area Qualifier and Regional championship organizers for the amateur motocross program, as well as Pro Motocross promoters.

“So, it was easy for us to rally the troops and issue a call to action,” Russell said. “We had many Zoom calls with all the promoters.”

The Zoom call to announce the Safe-To-Race Toolkit quickly exceeded the Zoom capacity of 100 participants. A second call had to be scheduled.

“Motorcycle racing found itself as a ‘tweener,’” Cotter said. “We are not NASCAR. We are not NCAA football. We are not mainstream. So, we were able to somewhat fly under the radar, although we were very, very adamant that all of our organizers went through the front door, that they didn’t try to do things without permission.”

The key to that permission was the toolkit.

“This document spoke the language of the health departments,” Cotter said. “It didn’t speak our language.”

An event organizer or venue operator could take the document to the local health department, City Council, county officials or state government and point to the credentialed experts involved in producing it. Often, it was a better plan than the local authorities had drafted for their community, Cotter said.

Some health departments asked for tweaks. Some, including officials in New York, simply said, “No.”

But, overall, the Safe-To-Race Toolkit worked.

“Supercross was the first professional sports organization to go back and complete its series,” Leale said. “We used the bubble method in Salt Lake City to make that happen, without fans. And then the Pro Motocross Championship and all the amateur races that occurred.

“The fact that we were able to complete a championship that started, then stopped, and then start a championship that hadn’t started yet and, not only complete it, but complete it making adjustments on the fly, you know, we weren’t supposed to race at Loretta’s twice, but we did, and that’s a testament to the fact that we had a plan.

“We were able to go to a place initially, and they were comfortable with us coming back and racing there again, because it was proven that we were doing things the right way.”

Russell said her companies’ programs benefitted from the racers’ passion.

“We had a record year for entries in the 40-year history of GNCC,” she said.

Assessing The Outcome

“We really learned a lot through this entire experience—a lot of protocols that we are going to continue,” Russell said. “When this whole pandemic and this virus is gone, we’re going to continue a lot of the protocols that came out of the task-force toolkit. They made us a better series in a lot of ways. They’ve made race administration more streamlined. Who would think there would be a benefit out of this? But there truly has been.”

Cotter said the process aged him 20 years.

“It was the most stressful thing I’ve ever done in my professional life,” he said. “It just changed so quickly. In the time we were on a call, something would change. And we were just banging our head against the wall.

“And I remember on a call, we realized that we were not equipped to do this. We’re a small family company in West Virginia. We’re a passion-based company. And this was way over our heads. But, because of our passion, we were not willing to give up. And that’s when we said, ‘Oh, let’s get help. Let’s get people that have credentials.’”

Russell said, “It was adapt or die. And our industry was able to adapt a lot faster than a lot of industries.”

Leale was particularly proud of the way the competitors handled the adversity.

“My role was, specifically, with the athletes and the managers and their management teams,” he said. “They were super positive, very open-minded.

“The sport of motorcycle racing is often very close-knit, and you have a lot of groups and secrets. But everyone was very open and worked great together.

“And the common theme to me—and I spoke to just about every single one of them—was that they were all, like, ‘Hey, we’re going to do whatever we’ve got to do to get back to racing.’ There wasn’t a single person or group that was negative about it. They understood what we were up against and what the promoters were dealing with and the racetracks and the venues and they were like, ‘Whatever we’ve got to do, we’ll do it. It’s not a big deal.’

“I wouldn’t say they liked everything we had to do. But that’s not what it was about. They knew we had to do it.

“They were all very professional,” Leale said. “It’s a testament to the kind of people we have in racing.”

Safe-to-Race Task Force Members

AMA:

Bill Cumbow, Mike Pelletier,

Alexandria KovacsDAYTONA MOTORSPORTS GROUP:

Gene Crouch,

Jared Johnson and Joey MancariFeld Entertainment:

Dave Prater

Ignite Partners:

Ken Hudgens

and Tim MurrayMotorsports Reg:

Brian Ghidinelli

and Chris RedrichMX Sports:

Tim Cotter,

Jeremy Holbert and Jeff CanfieldMX Sports Pro Racing:

Davey Coombs, Carrie Russell and Roy Janson

Mylaps:

John Dains and Gabe Ellett

Pro Motocross Organizers:

Amy Ritchie and Alan Verlander

USMA:

Robert Johnson

and Shawn StewartRider Representative:

JH Leale