American Motorcyclist May 2018

Look & See: Motorcycles Are Everywhere

Distracted Driving Is Deadly Driving

► AMA members get exclusive access to American Motorcyclist every month! Join The AMA Today!

Illustration By Gina Gaston

By Jim Witters

Whenever you are riding near other vehicles, chances are there is a distracted driver in the area.

During daylight hours, approximately 660,000 drivers are using cell phones while driving, according to data gathered by the federal government.

We’ve all seen drivers using cell phones for talking and texting behind the wheel. But a cell phone is far from the only distraction for drivers. Eating, drinking, talking, applying makeup or fiddling with the vehicle navigation system all take drivers’ minds and, often, their eyes off the road and nearby vehicles.

Some people have even admitted to watching streaming video services while driving.

May is Motorcycle Awareness Month. Launched with AMA assistance in the early 1980s, Motorcycle Awareness Month has been adopted by state motorcyclist rights organizations, local and state governments and AMA-chartered clubs.

Awareness is a broad issue that encompasses many aspects of riding and driving. But by far the hottest topic today is distracted driving.

Whether you are in your car or on your bike, whether you are a driver, rider, passenger or pedestrian, distracted drivers put you at risk.

Even if you don’t ride on the street, you likely use public roadways to get your dirt bikes or ATVs to the trails.

Nationally, teens were the largest age group reported as distracted at the time of fatal crashes. But all age groups are responsible for their actions on the road.

National Initiative Underway

The Risk Institute at The Ohio State University Fisher College of Business is leading a nationwide initiative to predict and curb distracted driving behaviors.

The AMA is involved in the effort to ensure motorcyclists are considered in the research and included in any proposed policies or legislation that results. Dozens of companies, government entities and researchers also are part of the discussion.

During a daylong event in February in Columbus, Ohio, panelists presented their preliminary findings on some of the factors that contribute to the practice of driving while distracted.

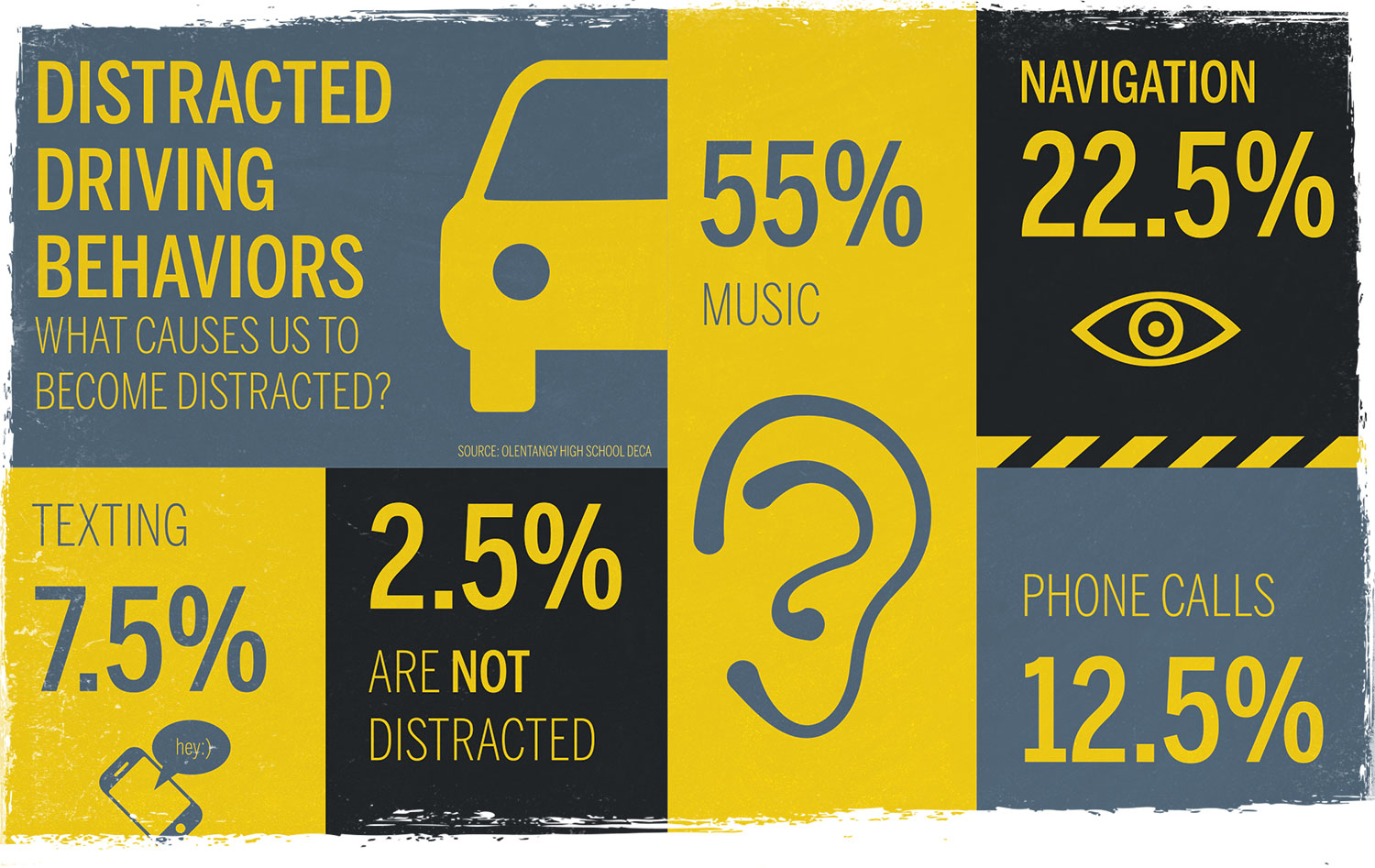

A small, informal study by a group of students at Olentangy High School in Ohio found that the most common use of a cell phone while driving was to get directions. But the second most common distraction reported by their classmates and their parents was searching for music.

Some people use cell phones to control in-car music. Others use those big dashboard screens. But even the old push-button AM/FM radios and CD players can be distracting.

And Sirius XM radio now offers an on-screen menu that displays the songs playing on all the channels—one more temptation to take your eyes off the road and your mind off driving for longer periods of time.

Texting and calling, which most people associate with distracted driving, was third on the list.

All of these behaviors increase the potential for deaths and injuries on U.S. roads. Motorcyclists are among the most vulnerable road users.

At the same time, though, riders must do their part to remain vigilant on the road. Bluetooth devices, stereos, GPS units and other useful or entertaining gadgets can distract motorcyclists just as easily as car or truck drivers. And those distractions can prove just as dangerous.

Kids And Parents Roles

Kids And Parents Roles

The Olentangy study started as a creative marketing project and expanded into involvement with The Risk Institute effort. Four seniors—Emily Gernert, 18, Olivia Giles, 18, Emma Brown, 17, and Justin Rehklau, 17—persuaded their parents, fellow students and the parents of those students to use a smartphone app to track their driving and to self-report distractions behind the wheel.

Once the findings were in, the four launched an awareness campaign that included public service announcements at the school, bulletin board messages, a video and use of the school’s outdoor marquee.

The result: “What we did was not effective,” Gernert said.

“We discovered that the problem was deeper and much more than something that could be taken care of with just one solution,” she said. “The path we were trying to go down was too simple and traditional to be effective for this issue.”

What Is Distracted Driving?

Distracted driving is any activity that diverts attention from driving, including talking or texting on your phone, eating and drinking, talking to people in your vehicle, fiddling with the stereo, entertainment or navigation system—anything that takes your attention away from the task of safe driving.

Sending or reading a text takes your eyes off the road for 5 seconds. At 55 mph, that’s like driving the length of an entire football field with your eyes closed.

You cannot drive safely unless the task of driving has your full attention. Any non-driving activity you engage in is a potential distraction and increases your risk of crashing.

Source: www.distraction.gov

The group changed course.

“We decided to shift our focus to providing solutions and recommendations on the local, state and national levels,” Giles said. “While creating those recommendations, we focused on three main goals: Putting an emphasis on creative marketing [such as reaching out to people in more effective ways], defining a key source of the problem and increasing education and knowledge for all ages.”

Some of those proposed solutions include the use of distracted-driving simulators to educate motorists, arranging educational meetings for parents, scheduling two distracted-driving seminars a year for high school students—an elective course that includes use of a simulator—passing legislation to make distracted driving a primary offense and increasing the discussion of distracted driving in driver education courses.

But the Olentangy project also identified a key role for adults.

“Family is the No. 1 influence in a child’s life, and parents are the most significant role models for their children,” Gernert said. “Before kids get behind the wheel to learn how to drive for themselves, they spend 15 years as passengers in the car with their parents and other adults.

“Throughout those important years of growing, learning and maturing, they watch and observe others driving and will adapt the behaviors and habits of those drivers—specifically of their own parents—mostly because they believe that those behaviors are normal and right,” she explained. “It is crucial to reach out to parents, as well, in the effort to end and prevent distracted driving, because they are the root of the problem. In order to eliminate the issue, we need to change the driving behaviors of parents and adults.”

Tethered To The Phone

Tethered To The Phone

Brittany Shoots-Reinhard is a research associate at the Cognitive and Affective Influences in Decision making, or CAIDe, lab in the Department of Psychology at The Ohio State University. Her presentation to The Risk Institute dealt with some of the reasons people feel compelled to fiddle with their phones while behind the wheel.

“People can get emotionally attached to their phones,” she said. “The people who have high attachment could be distressed or uncomfortable if they forget their phone or would even rather lose their wallets than their phones. We found that this emotional attachment predicted distracted driving.”

Shoots-Reinhard likened the distraction of a cell phone to the way emails can disrupt workflow, “only with vastly more dangerous consequences.”

“It could be thinking that the benefits of looking away for ‘just a second’ outweigh the risks; it could be habit; it could be worry or fear about an emergency with family or work,” she said. “Once you hear a ding or buzz, you just want to know what it is. Even if you don’t answer, you’re thinking about it, and you’re distracted. That’s why apps or settings that disable those notifications while driving are so useful, because they prevent the distraction in the first place.”

Shoots-Reinhard and her fellow researchers set out to explore areas of distracted driving that had not been considered.

“Our approach has been to apply what we know about how people behave in general to this specific context,” Shoots-Reinhard said. “A lot of other researchers and organizations have very convincingly shown that distracted driving is dangerous, so we thought we could add to the research being done on the decision to drive distracted.”

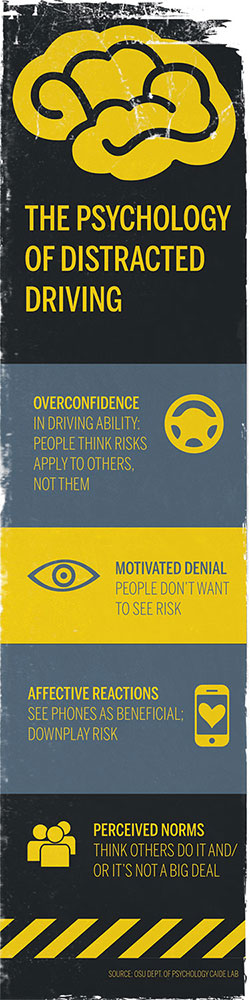

The research initially focused on people’s ignorance of the risks involved, overconfidence and lack of self-control.

In the fall of 2017, Shoots-Reinhard and her colleagues conducted a survey that included a few hundred drivers. The survey asked the participants about their risk perceptions, overconfidence and attitudes about their phones and driving.

“We also gave people some information about distracted driving to see if people who drive distracted are motivated to disbelieve that their behavior is risky,” she said.

Two key findings emerged.

“First, there are a lot of factors that predict distracted driving,” Shoots-Reinhard said. “Everything we’d hypothesized would predict distracted driving we found evidence for.”

Greater distracted driving was associated with lower perceptions of how risky distracted driving is, greater overconfidence in distracted driving ability and greater attachment to cell phones, she said.

“We also found that people who drive distracted think others do, too,” she explained. “On the bright side, behaviors that we often see as particularly risky was low. Drivers said they did things like sending texts and watching videos less than 10 percent of trips, and most people said they never sent text messages or watched videos on their phone at all.”

The second key finding was “evidence of motivated reasoning.”

“The more people reported distracted driving behavior and the lower their risk perceptions of distracted driving, the less supportive they were of methods of reducing distracted driving,” Shoots-Reinhard explained. “Second, the less people supported methods of distracted driving and the less they perceived distracted driving as risky, the less convinced they were of evidence that talking on the phone while driving causes crashes.”

She said this second point is “critically important.”

“Our first instinct to convince someone that something is dangerous is to tell them how risky it is,” she said. “What other researchers have found, and what we’re seeing evidence of here, is that strategy is ineffective, at best, and can backfire, at worst.

“So members of the general public who don’t see distracted driving as problematic and who drive distracted themselves will resist attempts to convince them that what they’re doing is dangerous and will not support policies that reduce distracted driving.”

Given those findings, modifying a driver’s behavior could prove difficult. Shoots-Reinhard offered a few insights into how that might be done.

“The best way to avoid giving into temptation is to avoid the temptation altogether—put your phone on ‘do not disturb’ while driving,” she said. “Even thinking about that screen or call is a distraction, and you’re using additional mental resources by not giving into the temptation.”

About The Risk Institute

The Risk Institute at The Ohio State University Fisher College of Business is a collection of companies and academics that help members consider risk from all perspectives: legal, operational, strategic, reputational, talent, financial and more. Members, faculty and students engage in an open, collaborative dialog about risk: its complexity, its relevance across all industries and its potential as a tool for competitiveness and growth.

Shoots-Reinhard said distracted drivers share some of the same traits as smokers who don’t believe their actions are dangerous.

“If we want to change people’s distracted driving risk perceptions, we can make emotional appeals— stories of victims and crash pictures—like we and others have shown increases smoking risk perceptions and quit intentions,” she said. “People who don’t think that distractions are risky are unlikely to voluntarily put their phones away.”

For that group, she said, “there is good evidence that fines for distracted drivers are effective deterrents, and our [survey] participants were supportive of punishing distracted drivers.”

“Enforcement also changes how socially acceptable it is to use phones while driving,” Shoots-Reinhard said. “We found that the more people thought others drove distracted, the more they drove distracted themselves. We won’t ride with drunk drivers, so we shouldn’t accept distraction, either.”

The bottom line: “It seems like, for motorcyclists, distracted driving is a hazard that others pose to them, rather than something that they can reduce.” But when you’re off the bike and driving instead, “put your phone away, and if you’re a passenger, ask that the driver do the same.”

Businesses Making Changes

Some businesses have already implemented Shoots-Reinhard’s recommendation.

Motorcyclist Stacy Emert is co-partner at InAlign Partners, a participant in The Risk Institute initiative and a member of the Delaware (Ohio) Teen Driving Task Force.

She said at least six companies have enacted strict policies on using handheld devices while driving on work-related assignments.

“Driving is a critical task that requires your full attention,” Emert said. “And insurance companies have pushed this, because they are losing $7 billion a year.”

Utility company NiSource has banned the use of cell phones for employees while driving on the job. AEP has adopted an “attentive driving policy” that includes no use of phones or hands-free technology. And Ohio Mutual Insurance Group enacted a pilot program that prohibits senior leadership from using cell phones in company-owned or leased vehicles.

“Companies see this as a no-brainer,” Emert said. “And we’re talking about sales people who are generating revenue and managers who are losing productivity by turning off their phones. But the lost productivity is worth it.”

As a motorcyclist, Emert is “tired of seeing foreheads” instead of the faces of drivers in oncoming vehicles.

“We think we are multi-taskers, but we are proven wrong, every time,” she said. “I ran off the road 19 times during a simulation, just changing my music selection.”

Technology: A Partial Solution?

Along with behavioral adjustments, experts have recommended apps that shut down devices in motion, in-car technology that disables devices and quicker adoption of driver-assist and autonomous vehicles.

While advancing technology can provide some safeguards, over-reliance on computer assistance may also encourage drivers to become more lax in their habits.

“I personally believe that the autonomous-vehicle technology will help prevent crashes,” said Wayne Allard, AMA vice president of government relations. “For example, technology that will automatically brake your car when driving too close will help.

What You Can Do

Everyone plays a part in reducing and, eventually, ending distracted driving.

AMA members should drive and ride safely at all times. Be aware of surrounding traffic and avoid distractions, whether behind the wheel or the handlebar.

Respond to AMA Action Alerts to let your elected officials know your stance on proposed distracted driving laws and regulations.

Read the AMA position statement on Distracted and Inattentive Vehicle Operation (www.americanmotorcyclist.com/

About-The-AMA/distracted-and-inattentive-vehicle-operation-1).

“But there may be flaws,” he continued. “Some designs use sensors that recognize vehicles in the middle of the road, so motorcyclists in the far left of the lane may be missed.”

In February, an Uber self-driving car struck and killed a pedestrian walking her bicycle across a four-lane street. Neither the technology nor the driver reacted in time to prevent the incident.

Many aspects of driver-assisted technology hold the promise of safer roads and fewer crashes. But introducing such features also allows drivers to relinquish direct control over the vehicle and can encourage them to disengage from surrounding traffic.

The AMA has called upon technology companies, software developers, car makers, legislators and regulatory agencies to consider and include motorcycles in the development, testing and deployment of new vehicle technology.

And the AMA signed a letter from the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers supporting the AV START Act (S. 1885) because it specifically includes motorcycles in its language and spells out the roles of state and federal governments in regulating the use of this technology.

The Senate bill requires manufacturers to file a safety evaluation report assessing the avoidance of unreasonable risks to safety of “objects, motorcyclists, bicyclists, pedestrians and animals.”

Legislation Pending

The AMA is tracking 45 bills in 16 states that relate to distracted driving this year.

The bills range from establishing rules for hands-free use of smartphones to increasing enhanced fines to creating enhanced penalties for causing injuries or death to “vulnerable road users.”

Some proposed laws eliminate age-specific restrictions and applies distracted driving laws to all drivers. Several apply to school zones. Some clarify that sitting at a red light and using a phone would be a violation. At least one state would make distracted driving a primary offense.

The law passed in Washington state is undoubtedly the strictest in the nation.

The law, which went into effect in July 2017, bans handheld uses, including writing or reading messages or email, sending or viewing pictures or transmitting data. Photography while driving is illegal. Drivers also are prohibited from using any handheld device while stopped at a traffic signal or stop sign.

There is no pending federal legislation aimed at distracted driving, but the U.S. Department of Transportation launched its fifth “U Drive. U Text. U Pay.” campaign in April, which the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has designated as Distracted Driving Awareness Month.

“A lot of effort has been put in by nonprofits and other road safety organizations to reduce road fatalities,” said Mike Sayre, AMA government relations manager for on-highway issues. “Federal road safety agencies support these efforts.”