AMERICAN MOTORCYCLIST MAY 2019

Do automated vehicles know we are here?

By Jim Witters

The concept of driverless vehicles promises a future free of crashes, where passengers use their time in transit completing business-related tasks, engaging in conversation, keeping abreast of the latest social media posts or streaming videos, while the vehicles make all the decisions and deliver their human cargo safely to their destinations.

Lane-keeping assistance, adaptive cruise control, blind-spot monitoring, steering assistance, automatic braking and more features already are available on cars and trucks being sold in the United States. And some of these features no doubt will help reduce the number of crashes, injuries and fatalities as vehicles become better able to communicate with each other, with smart roadways and with their drivers.

While experts say it will be years before many of these features saturate the market and even longer before fully self-driving cars are common on our roads, experimental vehicles are already on public roads for testing and pilot projects.

General Motors, Waymo, Tesla, Uber and other companies have put driverless cars on the roads of communities around the country.

In Columbus, Ohio, driverless electric shuttles, called Smart Circuit, are providing free rides to the public along a 1.5-mile route with stops at museums, a visitor center and a park. Each vehicle has an operator educating and assisting passengers, but who can also seize control of the vehicle.

The Kroger grocery chain is using unmanned autonomous vehicles to deliver groceries in Scottsdale, Ariz., in partnership with Nuro, a self-driving service.

The first commercial self-driving vehicles in New York are expected to begin operating in the Brooklyn Navy Yard this spring.

Yet there is no guarantee that any of them can detect motorcyclists and react properly to their presence.

“As the technological advances accelerate, little has changed from the regulatory perspective since the release of U.S. Department of Transportation’s Automated Vehicle 3.0, issued in October,” said Mike Sayre, AMA government relations manager for on-highway issues. “The federal government continues to rely on its Voluntary Safety Self-Assessment, which allows companies developing self-driving cars to decide whether their vehicles are safe.

“The idea of AV developers self-certifying many aspects of the safety of their vehicles, and the standards that they would be holding themselves to being totally voluntary and based on industry consensus, doesn’t exactly inspire a lot of confidence,” Sayre said.

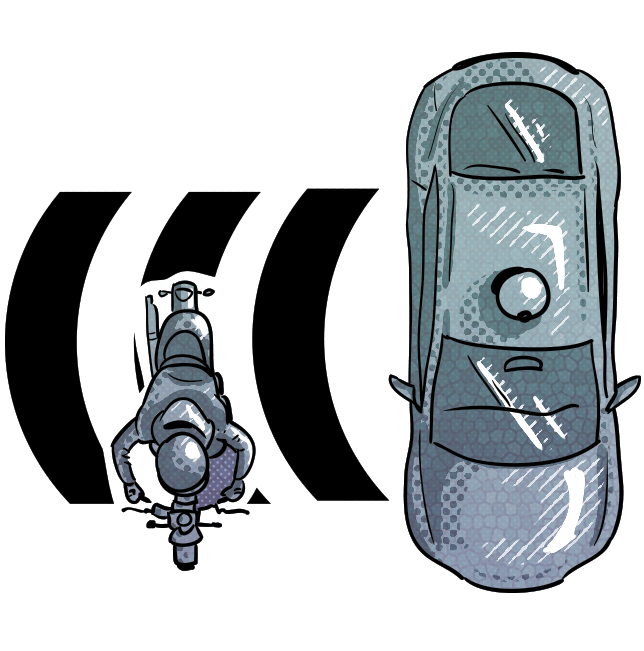

The National Transportation Safety Board issued a report in September acknowledging that motorcycles are not being considered in the development of crash-prevention technology, which is the basis for most automated-vehicle technology. The NTSB recommended that the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration work toward addressing this in vehicles and in smart infrastructure, as well.

Well-publicized incidents in which AVs were involved in crashes—some fatal—point to flaws in the software and in the drivers’ overreliance on it.

“The idea of AV developers self-certifying many aspects of the safety of their vehicles, and the standards that they would be holding themselves to being totally voluntary and based on industry consensus, doesn’t exactly inspire a lot of confidence”

Consumer choices

Driver-assist technology holds the potential to make the roadways safer for all motorists and motorcyclists.

For example, left-turn warning systems could alert drivers to an oncoming motorcyclist, reducing the frequency of one of the most prevalent types of motorcycle-vehicle crashes.

At the Lifesavers National Conference on Highway Safety Priorities in April, Kenneth Bragg of the NTSB and others said that crash-prevention technology is poorly explained to consumers, who either do not understand the features’ capabilities or abuse them, if they do.

“This leads to complacency and higher risk when the drivers need to take over operation of the vehicle,” Sayre said. “If a car is great at stopping for a another stopped car that is totally in line with it, a driver may pay less attention when the car fails to stop as well for a turning car in front of it.”

For example, Tesla cars cannot drive themselves. But the name of the driver assist feature is Autopilot, which could easily lead consumers to assume the car is capable of much more than it is.

A report from Axios AV editor Joann Muller details the NTSB and NHTSA investigations into three Tesla crashes: A March 1 incident in which a man died when his Tesla drove under a semitrailer that was crossing a Florida roadway; a 2018 incident in which a Tesla crashed into a highway barrier in Mountain View, Calif.; and another 2018 incident in which a Tesla crashed into a stopped fire truck in Culver City, Calif.

If the Tesla technology is unable to prevent crashes into trucks and roadside barriers, the prospect of these vehicles avoiding motorcycles seems small.

Even if the technology is effective, studies show that many drivers disable the features, Sayre said.

A survey released in January by Esurance found that one in four drivers who wanted high-tech features in their cars have deactivated at least one feature.

And, overall, drivers with in-car technology tend to be slightly more distracted than those without it. The survey showed that 29 percent of respondents found the warning sounds themselves can be distracting.

What’s being done

The AMA has focused on convincing vehicle manufacturers and software developers to ensure that motorcycles are accounted for in their technology.

And the AMA has been pressing elected officials and federal regulators to hold companies accountable.

At the same time, a number of AMA members were appointed to the federal Motorcyclist Advisory Council. And Sayre was appointed MAC chair.

The MAC will speak out on behalf of America’s motorcyclists in the areas in which it is authorized to advise the Secretary of Transportation.

“The SMRC is taking a holistic approach to motorcycling safety. we are not just focusing on motorcycle technology, but will be looking at all aspects that have an influence on rider safety.”

Two other groups—one in the United States and one based in Europe—have emerged to address the way motorcycles will interact with other vehicles and smart roadways in the future.

The Connected Motorcycle Consortium, based in Germany, was founded in 2016 when BMW Motorrad, Honda and Yamaha agreed on the need to improve motorcycle and scooter safety. Joining the three founding members are KTM, Triumph, Suzuki and Ducati.

Those in the group recognized that motorcycle safety was not being sufficiently considered in connected mobility, vehicle-to-vehicle communications and what it calls cooperative integrated transportation systems.

“CMC aims to create a common basic specification for motorcycle [intelligent transport systems], with as many cross-manufacturer standards as possible,” the group’s website states.

The goal is to introduce powered two wheelers equipped with cooperative integrated transportation systems by 2020.

In the United States, the Safer Motorcycling Research Consortium was founded this year by American Honda Motor Company, BMW Motorrad, Harley-Davidson, Indian Motorcycles, Kawasaki Motors Corp. USA, and Yamaha Motor Corporation USA.

Mike Hernandez, Safety Standards and ITS Technical manager at BMW of North America, is chair of the board for the consortium. He said the SMRC will be working with the CMC, as well as initiating its own projects.

Mike Hernandez, Safety Standards and ITS Technical manager at BMW of North America, is chair of the board for the consortium. He said the SMRC will be working with the CMC, as well as initiating its own projects.

“The SMRC is taking a holistic approach to motorcycling safety,” he said. “As evidenced by our name, we are not just focusing on motorcycle technology but will be looking at all aspects that have an influence on rider safety.

“By way of example, we may consider improvements to passenger cars to better detect motorcycles, enhancements to rider training programs, improvements to infrastructure, rider equipment and any other aspects of the motorcycle riding ecosystem that might save lives and reduce injuries.”

SMRC initially was formed with the intent of operating along the lines of the federal Crash Avoidance Metrics Partnership model, which involved collaboration between the industry as project lead and NHTSA as advising partner, according to Hernandez. Both parties contributed to funding.

“In the case of the SMRC, we intend to follow a similar setup,” he explained. “However, NHTSA has indicated that they may conduct research independently, with SMRC in an advisory role, so 100 percent of the funding would be from the government.

“Of course, the SMRC is not opposed to this concept, however, we don’t intend to rely on NHTSA for funding all of the research. In the case of CAMP-style funding, we would then disburse grants to research partners as needed.”

Since both BMW and Honda manufacture motorcycles and cars, their perspective will help form the SMRC effort, Hernandez said.

Anti-trust laws prohibit the companies from sharing proprietary technology that is being used on member vehicles.

The SMRC will be examining the existing research done by the federal government—for example, the NTSB Safety Report (SR-18/01) and the ITS-JPO Gap Analysis (FHWA-JPO-18-700)7—that could lead to the development of specific technology.

“In the near term, we are considering evaluations of the existing passenger car sensor systems in their ability to detect motorcycles,” Hernandez said. “For example, can a car’s blind spot monitor detect motorcycles sufficiently?”

“Automated-vehicle technology holds promise for improving motor vehicle safety and saving lives, but only if it is implemented correctly and in a manner that considers all elements of the traffic mix.”

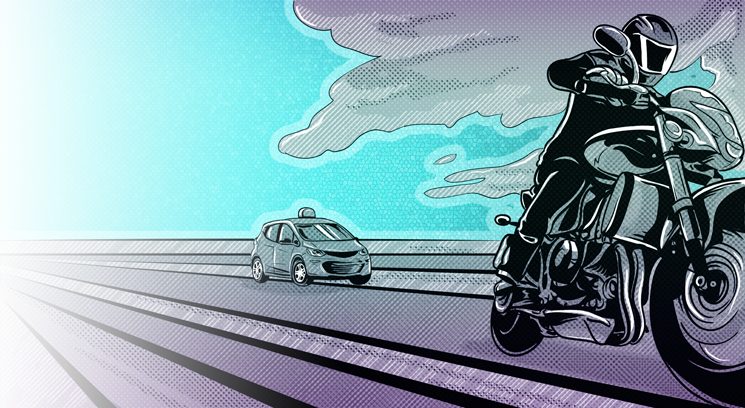

The future

No doubt, AV technology has the potential to be effective at reducing the number of non-motorcycle crashes and fatalities, Sayre said.

The AMA concern is that this technology will continue to be rolled out with little concern for motorcyclists, who are among the most vulnerable users of U.S. roads.

“Without the cooperation of the vehicle manufacturers and the tech companies, accompanied by more stringent oversight by federal regulators, future vehicles on America’s roadways will be inadequate for use in an environment shared with motorcycles,” Sayre said. “Automated-vehicle technology holds promise for improving motor vehicle safety and saving lives, but only if it is implemented correctly and in a manner that considers all elements of the traffic mix.”