AMERICAN MOTORCYCLIST December 2019

Protecting your brain

A Look At The Current Helmet Crop

When the first protective motorcycle helmet was designed by a University of South Carolina professor in 1953, the idea was to pad the user’s head inside a tough outer shell.

The following year, Roy Richter developed the Bell 500, and the motorcycle helmet industry was off and running. A decade later in 1964, the U.S. Department of Transportation issued its first standards for helmets.

Over the years, advances in helmet design and protection have been incremental. Most changes have focused on comfort, ventilation and measuring up to the DOT standard as well as voluntary standards, such as those established by the Snell Memorial Foundation.

Rotational Awareness

Perhaps the most significant leap in helmet technology, since that first protective helmet was built, occurred relatively recently. Many experts say those advancements are responses to the understanding that rotational acceleration in crashes is a major cause of brain injuries.

This shift in thinking was based on science. Both the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the European COST 327 study concluded that rotational forces are a principal cause of brain injuries.

With the revelations in recent years concerning the long-term effects of concussions and chronic traumatic brain damage, helmet manufacturers have gone full throttle researching ways to improve how helmets protect riders’ heads during crashes.

Although it has been around since the early 2000s, the Multi-Directional Impact Protection System—MIPS, for short—remains at the forefront of head protection research, said AMA Charter Life Member David Thom, a partner and senior consultant with Collision and Injury Dynamics Inc. in El Segundo, Calif.

The patented MIPS technology (www.mipsprotection.com), developed in Sweden, seeks to reduce brain injuries by accounting for the rotational acceleration that occurs during crashes.

While older motorcycle helmets were built to cope with linear forces generated by a direct impact, they did little, if anything to absorb the energy of the spin associated with impact.

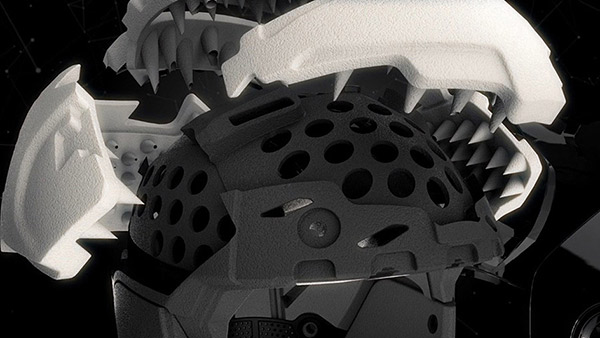

From top, the 6D ATS-1, Fly Racing Formula helmet impact liner, view of Fly Racing’s protective liner fit, and Fly Racing’s airflow

Linear forces will crack your skull or break your jaw. Rotational forces harm your brain.

Helmet makers using MIPS attempt to offset rotational forces by adding slick layers that mimic the fluid around the brain inside the cranium.

The system first appeared in motocross helmets and was adopted relatively quickly for competition use. But it has been slow to spread into street helmet applications.

Setting Standards

The most recent development in helmet standards came in June, when the Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme announced its FIM Racing Homologation Program for competition helmets.

Working with helmet manufacturers, the FIM devised a standard that it says “goes above and beyond” existing ones, such as those issued by the U.S. Department of Transportation, the Snell Foundation and the Economic Commission for Europe.

Unlike the DOT standard, the FIM does not allow manufacturer self-certification.

The FIM standard applies to all helmets used in circuit racing, including Grand Prix and Superbike racing.

The organization plans to extend its standard to helmets intended for off-road competition and, eventually, to non-competition helmets for street use.

The FIM’s foray into helmet certification has not been without debate.

Thom said the FIM should not be in the business of establishing helmet standards. However, he acknowledged the organization’s effort “did what other standards didn’t do.”

“The standard at least is an attempt to address rotational acceleration,” he said.

From left, the LS2 MX470 Subverter, the LS2 Subverter Matte Black and the LS2 Straight Blue/Black Hi-Viz

Crossing Disciplines

The FIM joined the National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment—which tests helmets for the National Football League—as the only two entities testing for rotational acceleration in helmets.

Implementation of the new standards has been delayed, Thom said. The FIM testing methods are being debated. And the NOCSAE standard faces “technical difficulties.”

Football helmets and motorcycle helmets are used in very different venues, but the associated risk is similar, Thom said.

“NFL players expect an impact on nearly every play,” he said, “but riders go days, weeks, months, years, even decades without striking their heads. And helmets are the only things that can help protect the head when an impact occurs.

“The standards are still developing, and this is a very active area of helmet research,” Thom said.

Aside from the evolving standards, motorcycle helmet users benefit from lighter materials that reduce neck fatigue, electronic upgrades for navigation and hands-free communications and built-in sunshades and other conveniences.

“I’m a big fan of making an acceptable helmet,” Thom said. “How big do they have to be to provide adequate protection? How big a helmet will we wear? It’s always a balance of size, weight, coverage and protection.”

Here is a look at a few of the modern helmets available now.

6D Helmets

6D Helmets developed its proprietary Omni-Directional Suspension technology in the early 2010s. The company continues to improve the system and has received some notable recognition for its efforts.

ODS helps reduce energy transfer to the brain by placing a set of dampers between the outer polypropylene layer and inner polystyrene layer. 6D began developing the system in 2011 and it was first used in the company’s production helmets in 2013.

Derek Radel of 6D said the company’s newest off-road/MX helmet, the ATR-2, features updated ODS technology.

The new ODS system allows for more helmet rotation during a crash and better absorbs the energy from linear helmet impacts than the previous version.

Another new feature of the ATR-2’s EPS liner—the innermost layer of the system’s three-layer ODS system—can be rebuilt if a helmet’s shell is undamaged. This can save an off-road rider hundreds of dollars over the life of a helmet, especially in recreational or racing disciplines where light crashes are common.

6D and the independent testing laboratory it works with, Dynamic Research Inc., were named the winners of the Head Health Challenge III in 2017.

The Head Health Initiative is a four-year, $60 million collaborative effort between the U.S. Commerce Department’s National Institute for Standards and Technology, the National Football League, General Electric and Under Armor to spur innovation in student, athlete and military head safety.

Dynamic Research and 6D won a $500,000 prize for their efforts, beating out 124 other teams.

Fly Racing

Fly Racing’s response to the need for adequate rotational impact protection is its proprietary Adaptive Impact System.

The multipart safety system was incorporated into Fly’s Formula helmet model, which was released in January 2019.

The AIS system is designed to offer superior protection from a wide range of impact angles and speeds, not just rotational impacts.

Instead of using a single EPS liner density, the AIS system uses Fly’s “conehead” technology, which incorporates combinations of EPS density for specific areas of the helmet. The result is a more progressive response from the EPS when it is compressed during a crash. The progression of the EPS compression is intended to limit brain movement during a crash, which limits the frequency and severity of concussions.

Between a rider’s head and the EPS liner are seven impact energy cells. The cells are constructed of Rheon, which deforms and absorbs energy when compressed, such as during a helmet impact.

The outer shell of the Formula helmet is constructed of 12K carbon fiber, which offers a stiff, durable shell to compliment the multi-density EPS liner and soft impact energy cells.

LS2

Using new materials and densities is common in the evolution of motorcycle helmets. LS2 is going a more innovative direction and has incorporated nanotechnology into its off-road helmet manufacturing process.

The company’s President and CEO Philip Ammendolia said that LS2’s MX470 Subverter model has an outer shell that’s manufactured using nanotechnology to blend aramid fibers (a Kevlar-like substance) to a high-end polymer. He says that the process results in an outer shell that is strong but still flexible enough to work with the company’s other features.

The Subverter model, which was released in 2018, also includes LS2’s proprietary-but-MIPS-approved linear that allows the helmet to slide about for rotational impacts without using a separate MIPS liner.

LS2 also designed the Subverter’s chin bar to help absorb the energy of an impact.

“We introduced crumple zone technology that allows the chin bar to crush but not break, dissipating energy before it reaches the riders head,” Ammendolia said.

AGV Helmets

AGV’s AX9 helmet isn’t a typical off-road helmet. Nor is it simply an adventure riding helmet. It’s both.

Introduced in Dec. 2018, the AX9 has an innovative outer shell composite with the intended versatility to perform well on trails, fire roads, rural highways and interstates.

Unlike competitors’ shells, which tend to be made from only one type of material, the AX9 shell is constructed with a mixture of carbon, fiberglass and aramid to create a strong yet energy absorbent and lightweight shell. The AX9 is reported to tip the scale at 3.5 pounds.

What makes the AX9 so versatile is being able to set up the eye port area. The helmet can be equipped with a visor or used with off-road goggles. It also features a peak that can be adjusted or removed for highway riding.