riding feature

THE NATURAL

Three-Time AMA Motocross National Champion Marty Smith Was Fast, Friendly And California Cool

by John L. Stein

With his long hair, California surfer looks, smooth and fast riding style and sunny, easy-going demeanor, Marty Smith went from high school student to Honda factory motocross racer and the guy everybody wanted to be, every girl wanted to be with and every racer wanted to beat in the mid-1970s.

In his six years with Honda, he won three motocross national championships—two in the 125cc class, one in the 500cc class—and narrowly missed a fourth championship in the 250cc class.

Following a career-altering crash in 1978, Smith opened a motocross school, stayed engaged with the sport, won the Baja 1000 with Larry Roeseler and Ted Hunnicutt Jr. in 1991, enjoyed his expansive friends network, raised a family, camped and drove his beloved sand rails.

He and his wife, Nancy, died in a buggy accident at California’s Imperial Sand Dunes on April 27. Smith was 63.

They leave behind three children, seven grandchildren and the love and appreciation of the American motocross community.

Golden state start

Smith was born in San Diego, Calif., a hotbed of talent in the early motocross years. He and future AMA 500cc national winner Tommy Croft attended the same high school and often practiced and raced together at area tracks, such as Carlsbad, Saddleback Park and Escape Country.

That Smith would take to motocross was not unexpected, because his parents, Al and Joan, volunteered at a local track and encouraged Smith‘s growing passion.

A strong ride at Carlsbad on a Yamaha got Smith noticed, and he landed a ride with Swedish company Monark, whose 125s used Sachs engines.

What set Smith apart from legions of other teenagers in that period was his natural smoothness and speed on the bike. I can attest to this, having seen Smith aboard his Monark at Escape Country in 1972, during my own motocross debut.

It was hard to believe how fast and smooth a 15-year-old kid could be.

“He had so much determination and wanted to win,” said Honda teammate Croft. “He was a true racer.”

Up the ladder

Honda did not have a well-defined American race team at the time, but with the new Elsinore 125, company personnel knew they needed talent. They signed Smith to a contract while he was still in high school, letting Smith compete in the 1974 AMA 125cc nationals aboard a factory Honda.

Smith won the title that year and backed it up in ’75.

This immediate success validated Smith’s innate talent, speed, fitness and focus. As his career built and he moved from 125cc to 250cc and 500cc, his disposition never changed.

He never became arrogant or haughty; instead, he was always Marty. Fun loving, good-natured, generous with his time and loyal to Honda and to his friends.

As technology advanced, Smith adapted quickly and always maximized what the bikes could deliver.

Mechanic Dave Arnold recalled that Smith wasn’t particular about bike setup, though Honda did extensive testing and development between races. Instead, once at the track, Smith was generally good to go with the package at hand.

“I’d ask him if he wanted something done to the bike,” Arnold said. “He’d just say, ‘Whatever you think.’”

One of Arnold’s duties was to carefully position the clutch and brake levers on the handlebars, because Smith had figured out how to extract maximum corner speed from the bikes—pick a good rut, drop the bike in and gas it.

This meant Smith would often finish motos with the handgrips and levers scuffed from dragging in the dirt.

A Homebody at heart

Although racing professionally meant Smith had to fly often, he was hardly a jetsetter. In fact, during race weekends Smith, Croft and fellow racer Broc Glover often discussed how soon they could get on a plane and return to San Diego.

Smith was like a rock star who didn’t want to go carousing after the races—he just wanted to go home.

Glover recalls a Mount Morris, Pa., race where Smith essentially jumped off the bike and into their rental car still wearing his dirty motocross gear.

“He wanted to get home so badly,” Glover said, laughing. “He was changing out of MX clothes into street clothes on the freeway on the way to the Pittsburg airport.”

▲ Smith en route to his 1977 AMA 500cc motocross title.

Photo provided by Jim Gianatsis/FastDates.com

Rent a racer

Rental cars sometimes didn’t have it so good. Arnold recalled a race weekend at Red Bud where Smith excitedly drove into the pits with a muddy rental car, begging to show Arnold a dirt area with a tabletop jump that the car could be flown over, landing on the backside ramp.

Arnold declined, because he had to work on the bikes. When Smith returned, however, none of the doors on the rental car would open.

Further, the hard landings punched a hole in the oil pan and, with their return flight looming, Arnold patched it up as best as he could, filled the engine with racing oil and sent the riders on their way.

The rental car somehow made it to the airport as a steaming, overheated, muddy, bent beater.

A snaky proposition

Another glimpse of Smith’s playful side came unexpectedly in 1975. One day, Smith invited Glover, three years his junior, to a practice track with Honda’s Pierre Karsmakers.

Glover could scarcely believe he had been invited to join the illustrious duo in a private ride session.

Glover recalls a moment that signaled Smith’s fun-loving—and at times rowdy—character. Out of respect, as well as caution, they stopped riding as a rattlesnake slithered across the track.

But, just as the snake was heading down a gopher hole, without warning, Smith ran over, grabbed it by the tail and started pulling it out.

Glover and Karsmakers yelled for Smith to let go, imagining the lethal bite that would occur once Smith extracted the snake. Smith did let go, and the rattler continued safely down the hole.

“He later said, ‘I honestly don’t know what I was thinking!’” Glover recalled. “Since that day, we always laughed about it.”

Always in style

As a racer, Smith was fast and smooth, but never showy. Arnold remembers going on Honda photo shoots with him and then looking at the images.

“You could look at a hundred pictures of Marty, and there was not a bad one,” he said. “He was naturally fast and motivated to win. But he was also a ‘people person’—people loved him, and other racers wanted to be like him.”

Smith was also as clean a racer as he was precise in his riding. Though aggressive, he was not a dirty rider, like some of the period. He was so fast naturally, he didn’t need to employ ruffian tactics to aid his speed.

Ups and downs

Every racer has disappointments, and it is in their nature to remember these, almost more than victories. Among Smith’s was losing the 1976 125cc championship to Bob Hannah, who was riding a superior Yamaha factory bike with liquid cooling.

Honda was concerned about having its works bikes claimed, so it had issued Smith a more production-based bike that didn’t stack up.

The same year, Smith also traveled between America and Europe to race 125cc GPs, AMA 125cc motocross and the Trans-AMA series. It was all nearly too much, even for a kid in top condition.

Another disappointment was losing the 250cc championship in 1977 when a mechanical DNF skewered his points drive. But he rebounded to win the 500cc national championship the same year over Hannah, capturing titles at the bottom and top of the pro ranks in just three years.

Smith’s flame got turned down by a broken hip at the 1978 Houston Supercross, a serious injury made extra painful due to waiting in the infield until the main event concluded, and an even longer wait in the hospital before receiving attention.

Recuperation was no fun, either.

Shifting gears

Marty Smith hung it up after the 1980–81 seasons with Suzuki, focusing on the Marty Smith Motocross Clinic and enjoying friends, family and, eventually, grandkids.

A constant theme in Smith’s life was the good-natured disposition of his parents, who befriended everyone.

Whether by this family training or simply lucky genetics, Smith always remained friendly and sincere with people, including maintaining contact with old teammates and competitors, and always and forever inviting them to his beloved sand dunes to camp and drive buggies.

A man at peace

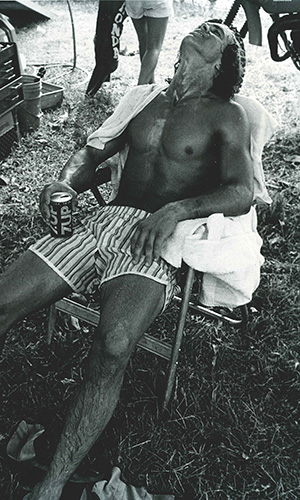

In a 2020 interview with photographer David Dewhurst—currently working on his book “Motocross: The Golden Era,” set for publication in 2021—Smith was happy, at peace and satisfied.

Only in his early 60s, he’d been through the wars and won, had a large loving family, innumerable friends and the prospect of more great times ahead. Relaxed on camera, he told Dewhurst, “I’ve got all the time in the world.”

Let us all be fortunate enough to live and value every day so fully as did Marty Smith.

John L. Stein is an AMA member from Santa Barbara, Calif.

▲ What a lineup! Kent Howerton (1), Danny LaPorte (7), Marty Smith (9), Bob Hannah (2), Roger DeCoster (104) and Tommy Croft (16).

Photo by Jim Gianatsis/FastDates.com