AMERICAN MOTORCYCLIST JANUARY 2019

Across The Channel

Riding the coasts of Normandy and Brittany

Bikes, beach & palm trees. Who could ask for anything more?

By Rick Wheaton

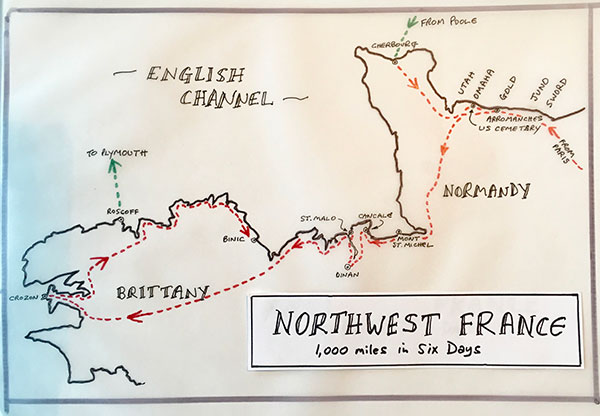

I’m lucky enough to live on the southwest coast of England, a coast l’ve loved and worked on all my adult life. But there is another coast, quite close, that l’ve also fallen in love with, the parallel one of Brittany and Normandy, sixty miles or so across the English Channel.

Like “my” coast, it’s a fascinating mixture of steep cliffs and sandy beaches, deep river inlets, safe anchorages and dangerous rocks. The Normandy beaches, of course, are specially interesting to Americans, in particular those code-named Utah and Omaha, chosen for the U.S. forces D-Day landings of 1944.

l first got interested in the landings in 1984, when—not far from my home—a complete WW2 U.S. Sherman tank was pulled out of the sea by local fishermen. Under water for 40 years, it had sunk during “Operation Tiger,” the disastrous rehearsal for the landings on Utah Beach—a rehearsal in which almost a thousand American servicemen lost their lives. This catastrophe seems incalculably worse when, just a few weeks later, fewer than 200 men died in the actual landings on the real Utah Beach.

The story of this training operation and how it went terribly wrong with such an appalling loss of life eventually became well known, despite decades of government and military denials. It got me interested in the landings, and l’ve always wanted to learn more.

Planning the ride

Fast forward a few weeks when my biker pal Ahmed (AM readers might remember him from those South America, New Zealand and South Africa rides) emailed to say he was at a loose end in the stifling 100-degree-plus heat of a Kuwaiti summer.

We quickly organized a weeklong Normandy & Brittany ride. He would be flying to Paris to hire a BMW 1200 from Hertz Ride, and I would be taking the car ferry to Cherbourg on my old faithful Tiger 800.

He was happy to leave the route to me, so we met up at Arromanches, the small Normandy seaside town that became the center of the largest amphibious operation in the history of warfare.

There’s a splendid D-Day museum here, packed with artifacts, superb models and tons of original equipment—even a cinema showing a documentary in four languages.

“Mulberry” jetty, a relic of the D-Day assault

History of the battle

For the D-Day landings on June 6, 1944, the allies chose five beaches along this 35-mile stretch of coast, and code named—west to east—Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword.

U.S. forces landed at the first two, and the other three were targeted by the Canadian and British.

This all took place in one day, and the simple statistics are absolutely mind-boggling: 6,900 vessels formed the sea-borne assault; they were supported in the air by 11,700 aircraft; the Allies together landed the staggering total of 159,000 men.

To repeat, all this in one day!

The success of this enormous operation was due in no small part to two artificial harbors that were towed across the Channel the previous night. Code-named “Mulberry,” each harbor consisted of 33 enormous reinforced concrete floating jetties linked by 10 miles of roadways.

Mulberry A was destroyed by a huge storm that hit the coast 12 days later, but Mulberry B—in more sheltered waters—survived, and, during the next 10 months, landed 2.5 million men, 500,000 vehicles and more than 4 million tons of stores and equipment.

Amazingly, even after 75 years, elements of Mulberry B have survived. The tides here are huge—a 25-foot range is common—and, at low water the next day, we walked around one of the concrete jetties, now washed up on “Gold” beach. Out at sea, some of the larger elements could clearly be seen, some weighing as much as 6,000 tons.

That afternoon we rode west along the coast to the Normandy American Cemetery at Coleville-sur-Mer, just above Omaha Beach.

The roads were narrow, bordered by high hedges and farmland, and, as we threaded our way through tiny peaceful hamlets, it was impossible to imagine the chaos and bloodshed of the landings.

More than 2,000 U.S. personnel were killed on Omaha Beach, alone (well known to anyone who’s seen Stephen Spielberg’s epic war movie “Saving Private Ryan”) and we spent a respectful hour at the impeccably manicured 175-acre memorial there.

As we walked out carrying our helmets, a friendly local told us there was a great exhibition of motorized equipment nearby, including BSA and Harley-Davidson motorbikes.

Sure enough, alongside the tanks and personnel carriers, we saw this terrific mockup of a battle scene, and center stage was a slightly knocked about 45 cu in V-twin Harley. Prized for their rugged strength, more than 90,000 of these WLA 45s—the single-seat, three-speed, chain-drive military variant—were made in Milwaukee.

A military Harley in a mock up at Omaha Beach

To Mont St. Michel and beyond

The weather was perfect that evening, and we continued west, a 120-mile ride across the bottom of the Cherbourg peninsula, aiming for the ancient towers of Mont St. Michel.

The cathedral itself is more than 800 years old, maybe one of those places so familiar from photos and movies that seeing them for the first time can be disappointing. Not so Mont St. Michel, it’s visible from 10 miles away, towering majestically above the surrounding landscape.

The land is so flat here, the incoming tides are dangerous if you’re on foot. Legend has it the sea will come in as fast as a galloping horse.

In the low evening sun, we rode a few miles farther, stopping for the night at Cancale, long known as the seafood capital of France, already looking forward to our evening meal.

Day 3 was an easy 80-mile circular ride, south across the River Rance to the beautiful medieval town of Dinan and back up to St. Malo.

On the way, we rode across the 2,500-foot barrage [a dam-like structure used to capture the energy from water moving in and out of a bay or river – ed.] built in 1966 for the tidal power station on the estuary. For 45 years, it was the largest of its kind in the world, and it still produces 0.12 percent of France’s entire electrical demand. Here at least, those big tides have come in useful.

The walled city of St. Malo is a fascinating place. Now a busy port and yachting center, its massive granite walls face the sea on two sides. For centuries the city was an impregnable fortress, home to pirates, privateers and wealthy merchants.

The city is almost an island, cut off from the rest of France, and there have been times when the citizens declared themselves independent and refused to pay their taxes. What could possibly go wrong?

Bombed heavily in 1944, St. Malo has been fully restored to its former glory, and the hour-long walk around the top of the huge walls is a must, even for bikers in boots.

Brittany and the trip’s end

Next morning, we pushed as far west as we could go. Our Day 4 ride was the longest, so far, at 240 miles to the Crozon peninsula.

This region of Brittany—a personal favorite—is called Finisterre (“end of Earth” or land’s end), a quiet unspoiled region of small villages, pleasant towns and pretty harbors nestled in a magnificent coastline.

Our plan was to stay here for two nights—time for laundry, shopping and a day unloaded to explore this beautiful area. It’s always good to throw off the heavy bag, clear out the panniers and ride light every now and then.

Our last day was another longish ride, 220 miles east along the northern Brittany coast, famous for its rose-colored granite outcrops.

More long sandy beaches, more pretty harbors, and our luck with the weather held.

The prevailing winds there are westerlies, and Brittany, along with Ireland and the southwest of England, gets more than its fair share of rain after the winds have crossed 3,000 miles of Atlantic Ocean.

Happily, we were enjoying a late dry summer, even parking by a couple of palm trees—it could almost have been Florida!

We spent our last night in France in the little coastal town of Binic.

From there, it was a stiff 285-mile ride for Ahmed back to Paris, but an easy 80 miles for me to Roscoff and my ferry across the Channel to Plymouth.

As we munched and slurped our way through another delicious dinner—one of the many reasons for visiting France—we looked back happily over the past six days and our thousand-mile ride — to be exact, 915 for me, and 1,120 for Ahmed.

Oh well, he’s half my age, it was good for him.

Rick Wheaton is an AMA member who writes about motorcycling and touring the world over.